Eric Hobsbawm spent his early years in Vienna

then in Berlin. Born in 1917 to an English father and an Austrian mother it was

in this crucible of pre-War Middle Europe that his life-long Communist views

were formed. He moved to England in 1930s and in time became England’s one

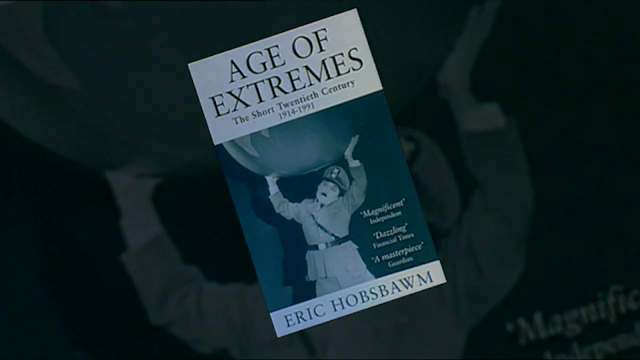

of most eminent historians, writing such seminal works as his account of the 20th

century, Age of Extremes. There are

few enough people left with his breadth of experience of the 20th century. So

when we met at the British Academy in London I asked him as a historian of

Imperialism what he thought of the world in which there is now only one real

empire.

ERIC HOBSBAWM: I've seen them come and I've seen them go. In the course of my

lifetime, all the old colonial empires went. The one empire which offered to

last 1,000 years lasted a good deal shorter. Another

great project, my own, which hoped to last for ever, didn't last for ever.

JEREMY PAXMAN: You're talking about

the Soviet Union?

HOBSBAWM: I’m talking about the

Soviet Union or world communism. So I don't give too much for the

long life of anybody declaring themselves a world empire. It will last my time,

but probably it won't last as long as some of the people that are going to read

my books.

PAXMAN: You talk about your own particular project. I bet you're

fed up with talking about this, but it is a legitimate area of questioning. You were, famously, a very long-standing member of the Communist Party.

Yet, everywhere one looks during the course of the 20th century, where

communism was applied it failed. Do you think your commitment was a mistake?

HOBSBAWM: My commitment to the cause of the poor, the oppressed,

wasn't. I think the solution that we thought we had

was a much more dodgy business. I thought at one time it was simply the historic

fact that it won first in some rather marginal and barbarous countries. There's

no question that made it much, much worse. If it hadn't been Russia, it would

certainly not have been anything near as barbarous as it was. On the other

hand, looking back, I must now say, I can't call myself a communist any more

because the kind of party

which I believed was necessary, which Lenin pioneered, and which was for a period in the 20th century an

incredibly formidable device for changing states and societies, has run out.

The historic period for that has gone. Nevertheless, the belief that

this is not basically a just society, it may be a tolerable society and it may

be a rich society and we live in lucky times and in a lucky part of the world

one shouldn't forget the others.

PAXMAN: The problem is the methodology, isn't it? No-one

disputes the ideals. Of course we would all seek a fairer world. But can you

think of anywhere where those principles were applied in practice which created

a society you admired?

HOBSBAWM: In some instances it created better societies.

PAXMAN: Where?

HOBSBAWM: I remember my friends

from India going to Soviet Central Asia and saying, "At least they've

taught them all to read and write." It may not seem much for us,

particularly now, as we can see there was a hell of a lot wrong and they were

poor.

PAXMAN: They taught them to

read and write but they didn't let them vote.

HOBSBAWM: They didn’t let them

vote but then the Americans didn't like to let the other people vote the wrong

way. It is a pity. I think the voting worries me less than the

absence of freedom of opinion, particularly a free press.

PAXMAN: What was it that made you decide to become a communist?

HOBSBAWM: Being in Germany between 1931 and 1933, living at a

time when it seemed clear that there was no solution for the problems of the

world, as I could see it as a teenager, which was not revolutionary. Living at

a time when not only did you know you were on the Titanic but you knew it was

going to hit the iceberg. The only question is what was going to happen when it

hit the iceberg. And it was almost impossible. Obviously, if I had been a

German, I might have decided to say, "Oh, well, I'm only interested in a

solution only for the Germans," and I might have become a Nazi. I could

understand why people in my school sympathised with this. I was English, and I

was Jewish on top of it so it didn't apply. Liberals, Social Democrats were not

on. Liberals were exactly what was failing.

PAXMAN: I can understand that in the context of Germany, with

Nazism emerging, that bi-polar intellectual or political world. But that wasn't

the world you found yourself in in this country. While membership of the party

must have been a warm embrace, it demanded a degree of fealty from you, didn't

it?

HOBSBAWM: You wanted to change

the world. You see, we were the first globalisers, we believed as, indeed Marx believed from the word go, that this is the way history was going, therefore

there must be global solutions. Even though, of course, we were concerned about

our own place, our own countries and so on. Nobody else produced

global solutions and when I came to England, there was the crucial question of

the fight against fascism, against the Nazis.

PAXMAN: Do you think it was a mistake to adhere to those beliefs

for as long as you did?

HOBSBAWM: It didn't make much difference, as far as I was

concerned. Whether I kept a party card, if you like, you know. I am not a

quitter by nature. That is one thing, if you want an answer. I wanted to stay to pay tribute to a

cause which was a good cause, a global cause. Never mind Stalin, never mind the

Soviet Union, never mind anything. It didn't make any difference to what I did

after. I went on doing what I had done before, teaching people, writing books

and I took very little part in politics. I am not a political figure, I don't

have the talent.

PAXMAN: To the extent that you did, through your work,

proselytise for that cause, do you now regret it, given that everywhere we've

seen it attempted it's failed?

HOBSBAWM: I did not proselytise

for the Communist Party, I proselytised against capitalism and for the

liberation of colonial peoples, for the poor, against the rich. I don't regret

that. Why should I?

PAXMAN: When you look at the world, with all of the edifices

that owed some sort of political antecedents to that belief, and you see this

single great capitalist power, what do you feel?

HOBSBAWM: I like America. I have worked in America, so, in a

sense, it is a nice country. It has its drawbacks. I am

sufficient of an old anti-imperialist to be suspicious of any world empires.

Particularly world empires that don't have anybody to keep them in check.

For the last 50 years, and it is lucky for us that this was so, there were two

world empires who kept themselves in check. One

was a more agreeable one, one would prefer to live under, the other was less

agreeable, but they kept each other in check. One has disappeared

and the net effect of this is, I think, the occupational disease of world

conquerors, particularly people that feel their military power is unlimited, namely

megalomania. There needs to be a learning curve because there are, even among

the officials of the United States, a lot of people who believe that world

empires live in the real world and the real world is a bit too complicated to

be run single-handed from Washington. I hope that that learning curve can start

or at least progress rapidly.

PAXMAN: Eric Hobsbawm, thank you.

This transcript was produced from the teletext subtitles that are

generated live for Newsnight. It has been checked against the programme as

broadcast, however Newsnight can accept no responsibility for any factual

inaccuracies. We will be happy to correct serious errors.

Your texts on this subject are correct, see how I wrote this site is really very good. https://mobilemob.com.au/blogs/news/5-000-steps-per-day-using-a-fitness-tracker-is-it-enough

ReplyDeleteIt's superior, however , check out material at the street address. Fitbit

ReplyDeleteLuckyClub Casino | Play for Free | Casino Site | 2021

ReplyDeleteLucky Club Casino is a top online casino site with lots of options for online luckyclub.live and mobile players. They have the highest RTP, high deposits, fast withdrawals,

This blog very easily understandable. Thanks for sharing such an informative post with us.

ReplyDeleteSelenium-training-in-hyderabad